You may have noticed that BeerXML, RecipeML, and Cookbook XML all have a <recipe> element. But those <recipe> elements are not the same. Each specification defines the child and sibling elements and allowed attributes (if any) in different ways.

Given that XML is a specification for writing markup languages rather than a language itself, and given that anyone – an individual or a community – can write an XML-compliant markup language, how are we supposed to know which <recipe> element is which?

The solution devised for XML is XML namespaces. A namespace is a way of saying which markup language an element belongs to. You can also think of it as an expanded element name.

<recipe> in BeerXML is really <BeerXML:recipe>.

<recipe> in RecipeML is really <RecipeML:recipe>.

<recipe> in Cookbook XML is really <Cookbook:recipe>.

We have confusing words in spoken languages also. Think about “pour.” In French, “pour” means “for.” In English, it means “to dispense fluid from a container or reservoir.” If languages were organized like XML, we could write “fr:pour” and “en:pour” to clarify which language we mean. Of course, we can work it out from context. But machines can’t make inferences from context the way humans can.

It would be a nuisance to have to expand the element name every time we use an element. Usually, we declare the namespace on the root element and then the processor (and the human reader too!) assume that all subsequent elements are in that namespace.

Exercise

- Open up your Oxygen application.

- Go to the File menu.

- Click on “New…”

- Scroll down to “Framework Templates” and click on the TEI folder

- Select “TEI simplePrint”

- You should now see a template document open in your editor window.

- Ignore the purple text at the top of the file for now. (We’ll come back to schemas later!)

- What is the root element?

- What attribute is on the root element?

- What is the value of that attribute?

Answers

The root element in any TEI-XML document is TEI (the only element in the Text Encoding Initiative’s XML-compliant markup language that is capitalized).

The <TEI> element bears an @xmlns attribute (for XML name space).

The value of that attribute is “http://www.tei-c.org/ns/1.0“. Notice that it is a URI? If you paste that URL into a browser, you will go to a page on the TEI’s own website: http://www.tei-c.org/ns/1.0 .

Namespaces were introduced in XML in 2003, as a way of allowing element names to be used in different contexts and still be unique across all contexts: “XML namespaces provide a simple method for qualifying element and attribute names used in Extensible Markup Language documents by associating them with namespaces identified by URI references” (https://www.w3.org/TR/2006/REC-xml-names-20060816/).

It was decided that namespaces would be identified by URIs, which are by definition already unique. In most cases, the URI resolves to a webpage on the website of the organization that maintains the XML standard.

If you use a <title> element in a TEI-XML file, you are really saying <http://www.tei-c.org/ns/1.0:title>. But because the namespace has been declared via the @xmlns attribute on the root element, we don’t need to keep spelling out that the elements belong to the TEI-XML language.

[What’s the difference between a URI and a URL? A URI is a “Uniform Resource Identifier” — a unique string that defines a digital object. A URL is a “Uniform Resource Locator” that defines and locates a digital object. All URLs are URIs, but not all URIs are URLs. (Okay, it’s a bit more complicated than that, but this definition will suffice for now!)]

Exercise

- Open up your Oxygen application.

- Go to the File menu.

- Click on “New…”

- Scroll down to “Framework Templates” and click on the DocBook folder

- Click on the DocBook 5.1

- Select “Article”

- You should now see a template document open in your editor window.

- Ignore the purple text at the top of the file for now. (We’ll come back to schemas later!)

- What is the root element? [Answer: article]

- What attribute is on the root element? [Answer: xmlns]

- What is the value of that attribute? [Answer: “http://docbook.org/ns/docbook“]

Using Two or More Namespaces in a Single Document

In this course, we are not likely to use multiple namespaces in a single document. But it’s worth knowing that you can do so. In fact, one of the motivations for developing XML namespaces is to encourage re-use and sharing of XML standards: “if such a markup vocabulary exists which is well-understood and for which there is useful software available, it is better to re-use this markup rather than re-invent it” (https://www.w3.org/TR/2006/REC-xml-names-20060816/).

If you use two namespaces, you need to declare both namespaces on your root element. Let’s keep working with the DocBook article template that you just opened. What if you wanted to introduce a TEI element into an XML article that is otherwise encoded in DocBook’s markup language?

The namespace that is already included in your template DocBook article file looks like this:

As you can see, the value of the @xmlns attribute is the URI of DocBook’s namespace.

The first thing you need to do is define both namespaces on your root element:

The error message provided by Oxygen says: “

| Description | Attribute “xmlns” bound to namespace “http://www.w3.org/2000/xmlns/” was already specified for element “article”. |

I’ve already added one @xmlns attribute to my <article> element. I can’t have two of the same attribute on one element!

TIP: An element can have only one of each attribute.

We qualify the attribute by making one @xmlns:d (for DocBook) and xmlns:tei (for TEI). I’m doing doing things here:

- I’m making my attributes unique.

- I’m defining a short form for my URI (because who wants to type http://docbook.org/ns/docbook at the beginning of every element?!).

Note that I get to make up the prefixes. I could use “doc:” instead of “d:” or “t:” instead of “tei:”.

Can you guess why my root element is now <d:article>? Answer: Because once I’ve started using two namespaces in my document, I have to add that prefix even to my root element.

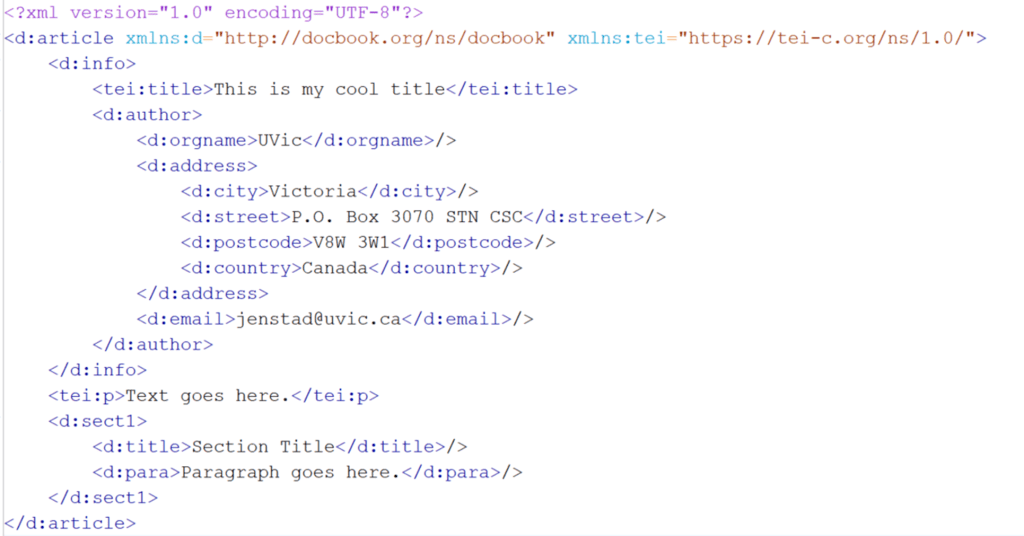

Here’s my sample document encoded in DocBook and TEI markup. It’s rather a silly example, because DocBook has a perfectly good element for encoding paragraphs: the <para> element. But if I really wanted to import TEI’s <p> element, I could certainly do so.

Where the ability to work in namespaces becomes particularly useful is when you are encoding something in a markup language that hasn’t anticipated your use case scenario. For example, TEI is amazing for encoding any text-bearing objects. It is not great for encoding the metadata for cartographic materials (e.g., maps). So one might want to import some tags from Metadata Object Description Schema (MODS) to capture map metadata. Likewise, if you have a snippet of music embedded in a literary file, you might want to use tags from the Music Encoding Initiative (MEI).